The Tyranny of Consensus.

Consensus is one of the most abused and misunderstood decision making tools executives use. Instead of being a method for insuring that every team member’s interests are given serious consideration, those in power often use it to cut short discussions to insure their own opinion is adopted by the group. How many times have you heard a boss say, “Well, it looks like we have consensus here – anyone disagree?” when you know that not everyone in the meeting has shared their ideas or agrees with the boss? There isn’t even a vote. That’s not even majority rule, let alone consensus. It is pseudo consensus and it can actually lead to cynicism and poor decision making (i.e., Challenger disaster, BP oil spill).

With many of today’s organizations trying to get away from the traditional command and control, top-down decision making processes in favor of more engaging processes, “consensus” seems to becoming the process du jour. It has become a catch-all phrase to describe almost any participatory decision making process. However, consensus is based on very specific assumptions and conditions and requires a highly skilled facilitator.

What is consensus.

The Latin origin of the word “consensus” means to feel together. With true consensus, everyone feels united about the decision. It is a process that enables a collective agreement by a group such that all the individuals can actively support the group’s final decision.

The collective agreement is based on listening to and accommodating, as best as possible, everyone’s interests. While many people mistakenly try to accommodate everyone’s demands or positions, the real goal is to accommodate their interests – their underlying reasons, needs or motives for the positions they take.

Consensus is not a negotiation. When groups try to accommodate everyone’s position, it usually ends up as a negotiation, with people horse trading (I’ll give you your demand on this if you give me my demand on that). Negotiating often assumes a zero sum game in which when I win, you lose and vice versa. Everyone is trying to get a piece of the pie. As a result, people compromise and often create a solution that is the lowest common denominator of all the knowledge and experience in the room.

Consensus, on the other hand, is based on collaboration, not compromise or horse trading. The goal is to make the pie bigger by creating a solution that goes beyond everyone’s self-interest and creates something of value for the organization or team as a whole. The goal is to create value, not to split the baby.

Consensus is based on the following two basic assumptions:

- Each person on the team has some part of the truth or an insight into the solution, and no one has all of the truth or knowledge necessary to make the best decision.

Especially as our organizations become more complex, globally diverse and virtual, it becomes more and more likely that no one person has the answer to many problems organizations face.

- Complete engagement and buy-in by all key stakeholders is critical to morale and to the successful implementation of the solution.

Consensus does not just mean that minority opinions are incorporated into the final decisions (or at least mitigated as much as feasible), it is also about the process of getting to that agreement. Team members need to feel the process allows for adequate advocating and debating of all opinions. When people feel their opinions have been understood, fairly debated and taken seriously by people they trust, they are much more likely to actively support the final decision even if they do not totally agree with all of the aspects of it (Brilhart and Galanes, 1989).

The goal of consensus is unity, not unanimity.

When people compromise, they often have mixed feelings about executing the decision. There may be unanimity about the decision, but there are unresolved conflicts that can impact execution.

When people collaborate, they end up willingly supporting the outcome. They are united. While everyone will not totally agree with all aspects of the decision, everyone can willingly and actively support it since the process gave them a sense of joint responsibility and ownership.

Common problems with consensus.

There are several common problems encountered when trying to make decisions by consensus and to achieve unity.

1. Groupthink

Groupthink occurs when people outwardly express agreement, but actually have doubts or reservations about the decision. They either feel obligated to go along with the group or want to avoid conflict.

2. The lowest common denominator.

When participants are not comfortable with conflict or change, they tend to only express ideas that are safe and conservative. They would rather hold back innovative ideas than risk looking stupid or deal with all the changes a truly innovative idea may require. In addition, collaboration could result in the elimination of innovative ideas that have not been tested, and people are unwilling to support it due to uncertainty. As a result, the lowest common denominator could become the only idea that unites people.

3. Social loafing.

Social loafing “refers to the negative synergy that occurs when group performance is less than the sum of the individual efforts.” (Latane, Williams and Harkins 1979) Research has found that people loaf or “hide in the crowd” when they do not think that their individual efforts will be adequately considered or evaluated. In addition, people are often not as motivated as when they work alone because they do not find the team’s work as personally meaningful or challenging enough to fully engage them. They also found that some people do not want to be perceived as a “sucker” (do a disproportionate amount of the work) so they pull back and do not work as hard as they could.

4. Inability to control who participates.

It can be difficult establishing boundaries around who can participate. For example, some people may complain they are not included in the process even if it unreasonable to assume they can add value. That is, it may be impossible to exclude some people for political reasons. Unfortunately, these unwanted participants could make achieving consensus difficult either because they have hidden agendas, they do not have the needed level of trust with other team members, they are not skilled at conflict management, or do not have the perspective of doing what is best for the whole team, not just their own interests.

5. Too large a group.

The size of the group can definitely impact the ability to reach consensus. Just hearing and debating everyone’s interests can become overwhelming and extremely time consuming. Particularly in globally matrixed organizations, keeping the group to a reasonable sized group of people who trust each other may be quite difficult.

6. Working virtually.

Trying to reach consensus in a virtual environment can be extremely difficult. Even if communications are synchronous, having everyone’s interests get a fair airing and maintaining engagement over the long period of time needed to discuss and debate issues is nearly impossible. In addition, it has been well documented that trying to manage conflict virtually is also difficult. When virtual teams also communicate via asynchronous media, the task becomes that much harder. Emails, text and Twitter are poor vehicles for communicating about emotional issues. When debating things in writing, people’s intentions are easily misconstrued. In addition, people may hold back their true concerns since an email, text or Twitter comment can be copied and sent to people all over the organization – some of whom have no context for the comments. In addition, social networking tools (texting, IM, etc.) makes it extremely easy for almost anyone on the team to give input at anytime, making it nearly impossible to put boundaries around the discussion.

7. Blocking.

Sometimes it is not possible to satisfactorily accommodate every minority interest and, as a result, one or more team members block consensus.

Clearly, there are numerous problems one can encounter when trying to reach true consensus. Therefore, it is important to attempt consensus only when certain key competencies and conditions are present.

What is needed to build consensus.

My colleague Rod Napier (personal communication) likes to say that reaching true consensus requires four things:

- Time

- Information

- Trust

- The ability to have good conflict

Reaching consensus usually takes significantly more time than other group decision processes. For example, it takes time to:

- Allow each point of view to be properly discussed and debated.

- Resolve conflicts.

Reaching a good decision also is highly dependent on having all the important information available to everyone. As a result, more than one meeting is often needed.

Consensus means conflict. When the process entails discussing and debating people’s underlying interests, conflict is inevitable. Conflict must be seen as a normal and healthy part of the process. Therefore, it is critical that team members are skilled and experienced at working through conflict. Unfortunately, most teams avoid conflict and most team leaders are not skilled at facilitating productive conflict.

Conflict is so inevitable, if some conflict is not present then either:

- The solution was obvious and there was no need to go through building consensus since there already was unity, or

- The group may be experiencing groupthink and avoiding conflict.

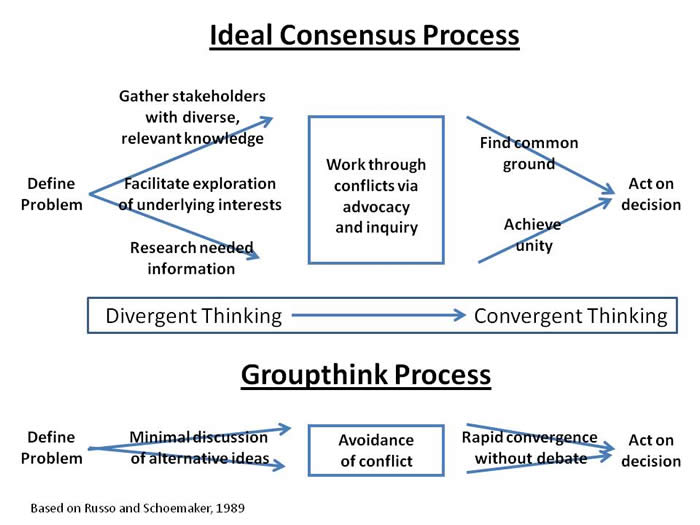

The difference between consensus and groupthink is displayed below:

President Kennedy’s response to two different crises is a great example of the role conflict can play in making sound decisions.

In April, 1961 Kennedy authorized the invasion of Cuba in an attempt to overthrow Castro. As everyone knows, it was a total failure. Although he had gathered a team of “the best and brightest”, all the information he was presented with had been filtered to reflect a positive scenario for an invasion. Although many feared the plan had many weaknesses, they did not speak up. Arthur Schlesinger, an historian and Kennedy advisor who witnessed the process, described it as “a curious atmosphere of assumed consensus.” Many key assumptions went unchallenged. For example, it was assumed that once the invasion began, Cubans would rise up against their government. Yet, there was a preponderance of evidence that this was not true. Kennedy never heard it.

On the other hand, 18 months later in the fall of 1962 he responded very differently during the Cuban Missile Crisis, during which the United States and the Soviet Union were on the brink of a nuclear war.

Kennedy assembled a more diverse team and demanded people argue their points of view. He included lower level officials so he could hear less filtered data. He was so insistent of getting unfiltered data, he often left the meetings so people would speak more freely. He even divided people into subgroups to research and advocate for different positions. Two people (Robert Kennedy being one of them) were assigned roles of being devil’s advocates to challenge every key assumption.

A key aspect of a peaceful settlement was the fact he even accommodated some of Khrushchev’s interests and needs by helping him save face (by giving up our missiles in Turkey). Most importantly, he and his advisors had the mindset of doing what was best for the nation and the world, and not to “win” or “beat the Soviets”. As a result, Kennedy and Khrushchev were able to find common ground (avoid a nuclear war in order to allow their children and grandchildren to live in a habitable world). Their common ground help avoid an unimaginable nuclear war. Talk about being able to “live with” the final decision.

Without a process that encourages and support conflict and debate, you get the Bay of Pigs and not the avoidance of a nuclear war.

Consensus demands a high level of trust among group members. They must believe that:

- Everyone has the best interest of the whole at heart and wants to collaborate

- No one has any hidden agendas and that everyone is honestly sharing their interests and motives

- Members have a grasp of problem and have information and/or a perspective that will add value to the discussion.

The need for a highly skilled facilitator.

In addition to time, information, conflict and trust, reaching true consensus is highly dependent upon having a very skilled facilitator.

It takes skill to overcome groupthink, social loafing, conflict and risk avoidance and all of the other dynamics that hinder building consensus.

For example, the facilitator must be able to manage what has been called the negotiator’s dilemma. In their book The Manager as Negotiator, Lax and Sebenius describe the dilemma as the tension between the need of people to claim value (getting as big a piece of the pie as possible) and creating value (make the pie as big as possible for the group).

That is, how much advocating does the facilitator allow for each person’s interests? When does advocating cross the line from productive debate to blocking cooperation?

When and how do you facilitate finding common ground? How does the facilitator switch the conversation from one of advocacy (“I am right and you are wrong”) to inquiry (“I wonder why you see things differently”)? It is critical that participants stop taking a position and begin to reveal their interests and motives. As stated above, only when people know each other’s interests can you begin to find common ground. It takes a highly skilled facilitator to contain participants’ natural tendency to want their idea to win in order to get them to maximize joint gain. No easy task.

In addition, the facilitator must be able to recognize the difference between consensus and groupthink. It takes a skilled facilitator know how to get hesitant team members to speak up when they may have given up or are avoiding conflict. It takes courage not to assume that agreement means everyone’s interests have been accommodated and run the risk of prolonging the discussion when it seems that consensus has been reached.

Thus, the facilitator must have many skills including the ability to:

- Read groups instantly

- Create an environment in which everyone’s views can be heard and debated.

- Help people reveal their true interests and motives so the discussion can move off of negotiating positions.

- Frame the problem and discussion in a way that opens up possibilities and does not bias the discussion to favor a certain solution. The discussion needs to focus on what is best for the whole team or enterprise.

- Manage productive conflict.

- Have the trust of the group.

- Make sure the right people are “in the room”.

- Know when more information is needed to come to the best solution.

- Maintain neutrality.

Reaching unity is not an easy task.

Viable alternatives to consensus.

As stated above, sometimes it is not possible to achieve true consensus. Maybe the interests of one or two people cannot be accommodated. Perhaps the group is too large or too geographically dispersed to have a good healthy debate. Or, there isn’t enough time.

Rather than wasting time and perhaps even damaging trust and morale trying to get complete unity, it may be better to switch to a different decision making process. Of course, knowing when to switch without creating more damage than not switching is a key judgment call. You would only want to do this on rare occasions since doing it frequently would make people doubt the sincerity of the leader’s commitment to consensus. Therefore, it is important to make sure the conditions are favorable for getting to consensus before you commit to using it.

Some alternatives to true consensus are:

- Consensus minus 1 or 2.

- This process can be used to prevent a group from becoming hostage to one or two people. While it can break a logjam, you run the risk of having two “losers” not supporting the decision.

- Consensus with qualifications

- When there is limited time or a relatively quick decision is needed, a leader can state that if the team cannot reach unity by a certain time, the leader will make the final decision. If team members feel that their interests have had a fair hearing and they have had a chance to influence the final decision, people are usually willing to accept and support the outcome. In discussing this approach, Eisenhardt, Kahwajy and Bourgeois their classic 1997 Harvard Business Review article “How Management Team Can Have a Good Fight”, found that executive team members “are willing to accept outcomes they dislike if they believe that the process by which those results came about was fair.” The authors found that leaders who announced this approach as the process the team will use for decision making were able to get some of the advantages of consensus without the need for a lot of time.

To be clear, consensus minus 1 or 2 and consensus with qualifications are not true consensus. With consensus minus 1 or 2, not everyone with minority opinions has had their interests accommodated. The minority may feel they are being forced to agree with an opinion with which they do not agree and cannot support. Consensus with qualifications leaves the leader, not the team as responsible or fully accountable for the decision.

Concluding remarks.

It seems like leaders talk about reaching consensus as if it was easy and that they do it all the time. I doubt it.

They may try to fool themselves into thinking their team has accommodated everyone’s interest, but I doubt they have. In fact, when presented with the scenario of the boss saying “Well, it looks like we have consensus here – anyone disagree?” I have never had a group of people not react with that knowing laugh that says “It happens all the time and I can’t believe my boss stupidly thinks everyone agrees!” It is pseudo consensus and everyone (maybe even the boss) knows it.

Silence is not consensus. Nodding your head is not consensus.

Reaching consensus takes hard work and a skilled team.

Remember the two key assumptions:

- Each person on the team has some part of the truth or an insight into the solution, and no one has all of the truth or knowledge necessary to make the best decision.

- Complete engagement and buy-in by all key stakeholders is critical to morale and to the successful implementation of the solution.

If these two assumptions are not true, use another decision making process. Using a ¾ majority rule can be the right process for a team if it isn’t critical that everyone’s interests are accommodated.

Just don’t go with the decision making style you are most comfortable with and you think is the popular way to go. Go with the decision making style that best fits the leader’s goals (how do you want people to feel afterwards, what do you want them to do), the sophistication of the team (how much knowledge do they have about the problem, what is their level of trust with each other, how skilled are they at conflict management), and the amount of responsibility and accountability that should belong to the leader alone versus the team as a whole.

Whatever decision-making process you choose, it is important to be clear with everyone which one you are using from the beginning. If it isn’t stated explicitly up-front, unnecessary misunderstands arise. There is nothing more trust-destroying than a situation where people think the decision is being made by consensus, but the leader changes the decision making process in midstream.

When done right, consensus is a powerful vehicle that builds unity and strategic alignment. When done incorrectly, it can create false expectations and hinder strategic execution.

|